Within the earlier article of this collection, operation in all fields of laptop science: matrix multiplication. It’s closely utilized in neural networks to compute the activation of linear layers. Nonetheless, activations on their very own are troublesome to interpret, since their values and statistics (imply, variance, min-max amplitude) can differ wildly from layer to layer. This is likely one of the the explanation why we use activation features, for instance the logistic perform (aka sigmoid) which initiatives any actual quantity within the [0; 1] vary.

The softmax perform, often known as the normalised exponential perform, is a multi-dimensional generalisation of the sigmoid. It converts a vector of uncooked scores (logits) right into a chance distribution over M lessons. We will interpret it as a weighted common that behaves as a clean perform and might be conveniently differentiated. It’s a essential part of dot-product consideration, language modeling, and multinomial logistic regression.

On this article, we’ll cowl:

- Implementing an environment friendly softmax kernel in Triton.

- Implementing the backward go (

autograd). - Optimisation: cache modifiers and auto-tuning.

In case you aren’t accustomed to Triton but, seek advice from the earlier articles!

Disclaimer: all of the illustrations and animations are made by the creator except specified in any other case.

Definition

The softmax is outlined as follows:

The normalisation ensures that the vector sums to 1, in order that it may be interpreted as a legitimate chance distribution.

Word that this formulation of the softmax is very delicate to numerical overflow. Recall that the utmost worth an ordinary float16 can characterize is 65 504, which is roughly exp(11). Which means that any enter worth better than ~11 will end in exp(z_i) exceeding the representable vary, resulting in overflow.

A typical trick to mitigate this situation is to subtract the utmost worth of the enter vector from each aspect, such that the brand new most is 0 earlier than exponentiation and 1 after.

Naive Implementation

As you possibly can see, computing the softmax includes two discount operations, a max and a sum. A naive algorithm require three separate passes over the enter vector. First to compute the utmost, then the sum, and at last the normalised outputs.

Right here’s what a naive Numpy implementation appears to be like like:

A recurrent theme on this Triton collection is minimising high-latency world reminiscence entry. Our present Numpy implementation requires three separate reminiscence reads of the complete enter vector, which is very inefficient.

On-line Softmax

Happily, we are able to use a intelligent trick, often known as the on-line softmax, to fuse the max and sum steps, decreasing the variety of reminiscence reads to 2.

First, we outline the sum of exponentials recursively. Within the following set of equalities, m_i refers back to the most over x till the i-th index.

This equality permits us to compute the sum of exponentials iteratively utilizing the utmost worth up to now. We will leverage it to fuse the primary and second loop within the naive implementation and compute the utmost and sum of exponentials iteratively.

Our algorithm turns into:

That is simply translated to Numpy:

Now that we perceive the principle ideas behind the softmax, we’ll implement it in Triton, beginning by the straightforward, single-block model and constructing as much as the web, multi-block formulation. In the long run, we would like our kernel to behave like a PyTorch module and be suitable with autograd.

Sadly, from PyTorch’s perspective, Triton kernels behave like black containers: the operations they carry out usually are not traced by autograd. This requires us to implement the backward go ourselves and explicitly specify how gradients must be computed. Let’s brush up on our beloved chain rule and derive the softmax gradient.

Gradient

For the reason that outputs of the softmax are strictly optimistic, we are able to use the logarithmic spinoff to make the derivation of the gradient simpler. Right here, we take the spinoff of the log of the output and apply the chain rule:

From there, we rearrange the phrases and comply with these steps:

Now assume that we’ve some upstream gradient, for instance generated by a loss perform L (e.g. a cross-entropy loss). We get the next expression of the gradient:

The simplification of the left time period in (9) is because of the truth that δ_ij will solely be equal to 1 for the i-th aspect, collapsing the sum over j to a single time period.

Triton Implementation

Single Block Softmax

Now that we labored via the derivation of the gradient, we are able to write the ahead and backward softmax kernels. First, let’s give attention to the PyTorch wrapper to know how the one block implementation works at a excessive stage. Given a 2D enter tensor, the ahead and backward kernels are going to course of all rows in parallel.

For simplicity, we’ll outline the BLOCK_SIZE to be massive sufficient to deal with all columns directly. Particularly, we’ll set it as the following energy of two superior to the variety of columns, as required by Triton.

Then, we’ll outline our `grid` to be the variety of rows (it might doubtlessly additionally deal with a batch dimension).

The PyTorch wrapper for our SoftmaxSingleBlock is a category inheriting from torch.autograd.Perform that implements ahead and backward. Each strategies take a ctx argument, which we’ll use to cache the softmax outputs throughout the ahead go and reuse them throughout the backward go.

Each kernels are fairly easy, we begin by loading the row inputs utilizing the identical syntax as in my earlier vector addition article. Discover that BLOCK_SIZE and num_warps are computed utilizing a calculate_settings perform. This perform comes from the Unsloth library and was reused in different kernel libraries corresponding to LigerKernel (which the kernels on this article are loosely primarily based on), it offers heuristics to tune each variables:

def calculate_settings(n: int) -> tuple[int, int]:

MAX_FUSED_SIZE = 65536 # most grid dimension on Nvidia GPUs

BLOCK_SIZE = next_power_of_2(n)

if BLOCK_SIZE > MAX_FUSED_SIZE:

# we take away this assertion on this article

elevate RuntimeError(

f"Can not launch Triton kernel since n = {n} exceeds "

f"the utmost CUDA blocksize = {MAX_FUSED_SIZE}."

)

num_warps = 4

if BLOCK_SIZE >= 32768:

num_warps = 32

elif BLOCK_SIZE >= 8192:

num_warps = 16

elif BLOCK_SIZE >= 2048:

num_warps = 8

return BLOCK_SIZE, num_warpsThen, we implement the common softmax for the ahead go and equation (10) for the backward go. The one novelty right here in comparison with earlier articles is the usage of cache modifiers, which inform the compiler find out how to cache and evict knowledge. For now, we’ll solely give attention to three cache modifiers:

.ca(Cache in any respect ranges): Tells the compiler to load the information in each L1 and L2 cache, suggesting that it is likely to be reused quickly. This modifier must be used when the information is sufficiently small to suit into L1 (~128–192KB per SM on an A100) and can doubtless be accessed repeatedly..cs(Streaming): Deal with knowledge as streaming, will probably be used as soon as after which discarded to unlock area in L1..wb(Write-back): Regular cached write, the information will stay within the cache hierarchy, good if the output could also be reused.

Within the following kernels, we’ll use the .ca modifier for masses since we carry out a number of operations on the loaded knowledge. For storing, we’ll use .cs within the ahead go, for the reason that outputs received’t be instantly reused and .wb within the backward go since within the context of autograd (i.e. the chain rule), gradient outputs can be consumed by downstream kernels.

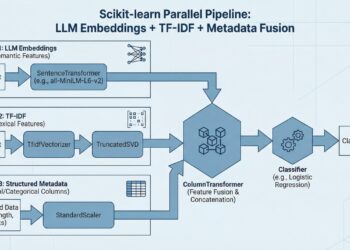

Multi-Block Softmax

Now, let’s check out the web formulation of the softmax. On this part, we implement a multi-block variant of the earlier kernel. This model will use BLOCK_SIZE < n_cols, in different phrases, we’ll solely load a tile with BLOCK_SIZE components at a time, just like how we dealt with tiled GEMM within the final tutorial. Now you may ask “how will we choose the block measurement?”.

This can be a nice event to introduce Triton’s autotune utility. Supplied with a listing of configuration, autotune will carry out a grid-search to find out and cache the most effective configuration for a selected enter form. This course of is repeated each time a brand new enter form is handed to the kernel.

Right here, we carry out a grid search over the block measurement and variety of warps utilizing the next utility perform:

from itertools import product

# --- Multi Block Tuning ---

BLOCK_SIZES = [256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192]

NUM_WARPS = [2, 4, 8, 16]

def get_autotune_config(

block_sizes: listing[int], num_warps: listing[int]

) -> listing[triton.Config]:

return [

triton.Config(kwargs={"BLOCK_SIZE": bs}, num_warps=nw)

for (bs, nw) in list(product(block_sizes, num_warps))

]We will now adorn our multi-block kernels with autotune and go the listing of configs, key=”n_cols” signifies that the optimum config relies on the variety of columns of the enter.

The implementation of those kernels is conceptually very near the web softmax we coated earlier than, the principle variations is that we iterate over tiles (not over single components like in Numpy), which requires some changes. As an illustration, we add a sum over the tile within the d replace and the backward kernel now requires two iterations as nicely.

Word: the PyTorch wrapper is precisely the identical besides we delete the road the place BLOCK_SIZE and num_warps are declared (since they’re picked by autotune).

Testing and Benchmarking

We will now execute a ahead and backward go with each kernels and guarantee they match the PyTorch baselines:

def validate_kernel(kernel_fn: callable) -> None:

system = "cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu"

torch.random.manual_seed(0)

# Generate inputs

x = torch.randn((256, 512), system=system) # triton enter

x.requires_grad = True

xt = deepcopy(x) # torch enter

triton_output = kernel_fn(x)

torch_output = torch.softmax(xt, dim=1)

torch.testing.assert_close(triton_output, torch_output) # check fwd kernel

# Setup pretend labels

y = torch.zeros_like(x)

inds = (torch.arange(0, y.form[0]), torch.randint(0, 3, (y.form[0],)))

y[inds] = 1

# Outline loss and run backward go

loss_fn = torch.nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

loss = loss_fn(torch_output, y)

loss.backward()

# Save gradient tensor for later

torch_xgrad = xt.grad.detach().clone()

triton_loss = loss_fn(triton_output, y)

triton_loss.backward()

torch.testing.assert_close(x.grad, torch_xgrad) # check grad outputs

validate_kernel(softmax_sb)

validate_kernel(softmax_mb)Lastly, we benchmark our implementation in opposition to the PyTorch baseline utilizing the next snippet:

# --- Supply: Triton softmax tutorial ---

@triton.testing.perf_report(

triton.testing.Benchmark(

x_names=["N"], # argument names to make use of as an x-axis for the plot

x_vals=[

128 * i for i in range(2, 100)

], # completely different attainable values for `x_name`

line_arg="supplier", # argument identify whose worth corresponds to a unique line within the plot

line_vals=[

"triton_single_block",

"triton_multi_block",

"torch",

], # attainable values for `line_arg``

line_names=[

"Triton_single_block",

"Triton_multi_block",

"Torch",

], # label identify for the traces

types=[("blue", "-"), ("green", "-"), ("red", "-")],

ylabel="GB/s", # label identify for the y-axis

plot_name="softmax-performance", # identify for the plot. Used additionally as a file identify for saving the plot.

args={"M": 4096}, # values for perform arguments not in `x_names` and `y_name`

)

)

def benchmark(M, N, supplier):

x = torch.randn(M, N, system=DEVICE, dtype=torch.float32)

stream = getattr(torch, DEVICE.sort).Stream()

getattr(torch, DEVICE.sort).set_stream(stream)

if supplier == "torch":

ms = triton.testing.do_bench(lambda: torch.softmax(x, axis=-1))

if supplier == "triton_single_block":

torch.cuda.synchronize()

ms = triton.testing.do_bench(lambda: softmax_sb(x))

torch.cuda.synchronize()

if supplier == "triton_multi_block":

torch.cuda.synchronize()

ms = triton.testing.do_bench(lambda: softmax_mb(x))

torch.cuda.synchronize()

gbps = lambda ms: 2 * x.numel() * x.element_size() * 1e-9 / (ms * 1e-3)

return gbps(ms)

benchmark.run(show_plots=True, print_data=True)Excellent news! Our single-block kernel persistently outperforms the PyTorch baseline whereas the multi-block variant falls off for inputs with greater than 6k columns:

Contemplating bigger inputs, we are able to make a number of observations:

- The multi-block kernel finally stabilises round 900GB/s of throughput, surpassing the PyTorch baseline for inputs with greater than 30k columns.

- Apparently, it looks like the multi-block variant will dominate for inputs with greater than 60k columns.

- Although we exceed the utmost block measurement with the single-block variant, the kernel nonetheless runs easily for some cause. Certainly, Triton robotically manages the block measurement underneath the hood.

Whenn_colsis bigger than the {hardware} restrict, Triton will break down the enter and iterate over it. Nonetheless, this appears to be slower than the multi-block strategy.

To go additional, we might mix each approaches in a single kernel that explicitly selects the optimum kernel primarily based on the enter measurement. This manner, we might profit from the excessive efficiency of the single-block kernel for small inputs and the upper throughput of the multi-block variant for inputs with greater than 60k columns.

This concludes the third episode of this Triton collection, thanks once more to your assist!

Within the subsequent article, we’ll leverage the web softmax formulation within the context of Flash Consideration.

Till subsequent time! 👋