On this article, you’ll find out how Python allocates, tracks, and reclaims reminiscence utilizing reference counting and generational rubbish assortment, and the right way to examine this habits with the gc module.

Matters we’ll cowl embody:

- The position of references and the way Python’s reference counts change in widespread eventualities.

- Why round references trigger leaks underneath pure reference counting, and the way cycles are collected.

- Sensible use of the

gcmodule to watch thresholds, counts, and assortment.

Let’s get proper to it.

Every little thing You Must Know About How Python Manages Reminiscence

Picture by Editor

Introduction

In languages like C, you manually allocate and free reminiscence. Neglect to free reminiscence and you’ve got a leak. Free it twice and your program crashes. Python handles this complexity for you thru computerized rubbish assortment. You create objects, use them, and once they’re not wanted, Python cleans them up.

However “computerized” doesn’t imply “magic.” Understanding how Python’s rubbish collector works helps you write extra environment friendly code, debug reminiscence leaks, and optimize performance-critical purposes. On this article, we’ll discover reference counting, generational rubbish assortment, and the right way to work with Python’s gc module. Right here’s what you’ll be taught:

- What references are, and the way reference counting works in Python

- What round references are and why they’re problematic

- Python’s generational rubbish assortment

- Utilizing the

gcmodule to examine and management assortment

Let’s get to it.

What Are References in Python?

Earlier than we transfer to rubbish assortment, we have to perceive what “references” really are.

Whenever you write this:

Right here’s what really occurs:

- Python creates an integer object 123 someplace in reminiscence

- The variable

xshops a pointer to that object’s reminiscence location xdoesn’t “comprise” the integer worth — it factors to it

So in Python, variables are labels, not containers. Variables don’t maintain values; they’re names that time to things in reminiscence. Consider objects as balloons floating in reminiscence, and variables as strings tied to these balloons. A number of strings could be tied to the identical balloon.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

# Create an object my_list = [1, 2, 3] # my_list factors to an inventory object in reminiscence

# Create one other reference to the SAME object another_name = my_checklist # another_name factors to the identical checklist

# They each level to the identical object print(my_list is another_name) print(id(my_list) == id(another_name))

# Modifying by way of one impacts the opposite (identical object!) my_list.append(4) print(another_name)

# However reassigning creates a NEW reference my_list = [5, 6, 7] # my_list now factors to a DIFFERENT object print(another_name) |

Whenever you write another_name = my_list, you’re not copying the checklist. You’re creating one other pointer to the identical object. Each variables reference (level to) the identical checklist in reminiscence. That’s why adjustments by way of one variable seem within the different. So the above code offers you the next output:

|

True True [1, 2, 3, 4] [1, 2, 3, 4] |

The id() operate reveals the reminiscence handle of an object. When two variables have the identical id(), they reference the identical object.

Okay, However What Is a “Round” Reference?

A round reference happens when objects reference one another, forming a cycle. Right here’s an excellent easy instance:

|

class Particular person: def __init__(self, title): self.title = title self.buddy = None # Will retailer a reference to a different Particular person

# Create two individuals alice = Particular person(“Alice”) bob = Particular person(“Bob”)

# Make them associates – this creates a round reference alice.buddy = bob # Alice’s object factors to Bob’s object bob.buddy = alice # Bob’s object factors to Alice’s object |

Now now we have a cycle: alice → Particular person(“Alice”) → .buddy → Particular person(“Bob”) → .buddy → Particular person(“Alice”) → …

Right here’s why it’s known as “round” (in case you haven’t guessed but). In the event you observe the references, you go in a circle: Alice’s object references Bob’s object, which references Alice’s object, which references Bob’s object… without end. It’s a loop.

How Python Manages Reminiscence Utilizing Reference Counting & Generational Rubbish Assortment

Python makes use of two most important mechanisms for rubbish assortment:

- Reference counting: That is the first methodology. Objects are deleted when their reference rely reaches zero.

- Generational rubbish assortment: A backup system that finds and cleans up round references that reference counting can’t deal with.

Let’s discover each intimately.

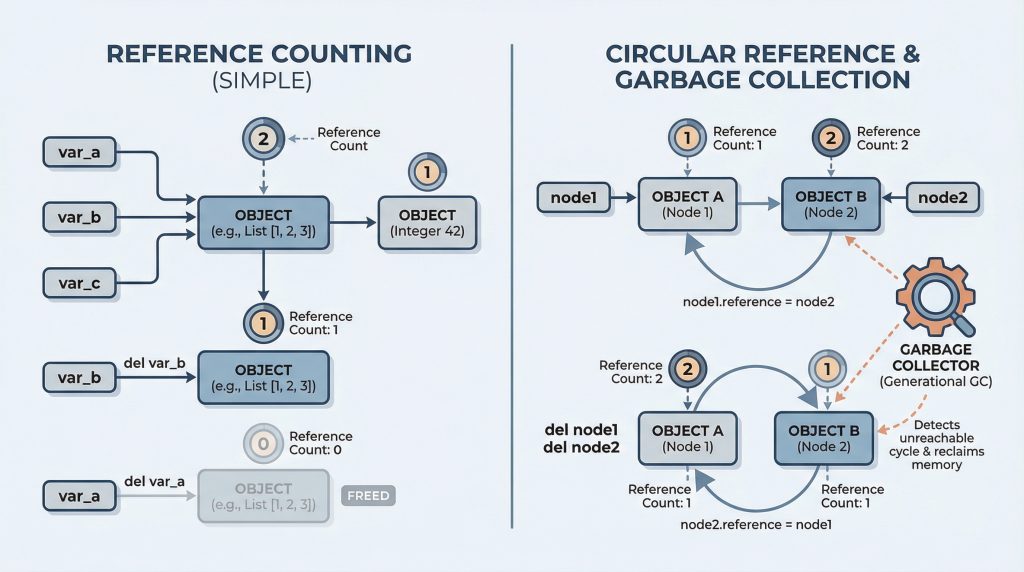

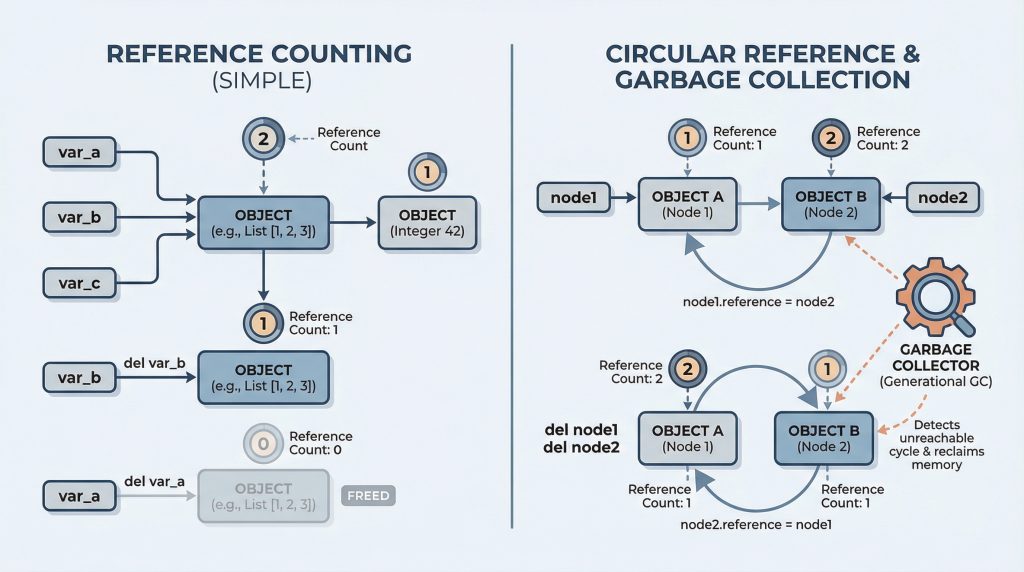

How Reference Counting Works

Each Python object has a reference rely which is the variety of references to it, which means variables (or different objects) pointing to it. When the reference rely reaches zero, the reminiscence is instantly freed.

|

import sys

# Create an object – reference rely is 1 my_list = [1, 2, 3] print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Create one other reference – rely will increase another_ref = my_list print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete one reference – rely decreases del another_ref print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete the final reference – object is destroyed del my_list |

Output:

|

Reference rely: 2 Reference rely: 3 Reference rely: 2 |

Right here’s how reference counting works. Python retains a counter on each object monitoring what number of references level to it. Every time you:

- Assign the item to a variable → rely will increase

- Go it to a operate → rely will increase briefly

- Retailer it in a container → rely will increase

- Delete a reference → rely decreases

When the rely hits zero (no references left), Python instantly frees the reminiscence.

📑 About

sys.getrefcount(): The rely proven bysys.getrefcount()is at all times 1 larger than you anticipate as a result of passing the item to the operate creates a brief reference. In the event you see “2”, there’s actually just one exterior reference.

Instance: Reference Counting in Motion

Let’s see reference counting in motion with a customized class that says when it’s deleted.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

class DataObject: “”“Object that says when it is created and destroyed”“”

def __init__(self, title): self.title = title print(f“Created {self.title}”)

def __del__(self): “”“Referred to as when object is about to be destroyed”“” print(f“Deleting {self.title}”)

# Create and instantly lose reference print(“Creating object 1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 1”)

print(“nCreating object 2 and deleting it:”) obj2 = DataObject(“Object 2”) del obj2

print(“nReassigning obj1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 3”)

print(“nFunction scope take a look at:”) def create_temporary(): temp = DataObject(“Momentary”) print(“Inside operate”)

create_temporary() print(“After operate”)

print(“nScript ending…”) |

Right here, the __del__ methodology (destructor) is known as when an object’s reference rely reaches zero. With reference counting, this occurs instantly.

Output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

Creating object 1: Created Object 1

Creating object 2 and deleting it: Created Object 2 Deleting Object 2

Reassigning obj1: Created Object 3 Deleting Object 1

Perform scope take a look at: Created Momentary Inside operate Deleting Momentary After operate

Script ending... Deleting Object 3 |

Discover that Momentary is deleted as quickly because the operate exits as a result of the native variable temp goes out of scope. When temp disappears, there aren’t any extra references to the item, so it’s instantly freed.

How Python Handles Round References

In the event you’ve adopted alongside fastidiously, you’ll see that reference counting can’t deal with round references. Let’s see why.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

import gc import sys

class Node: def __init__(self, title): self.title = title self.reference = None

def __del__(self): print(f“Deleting {self.title}”)

# Create two separate objects print(“Creating two nodes:”) node1 = Node(“Node 1”) node2 = Node(“Node 2”)

# Now create the round reference print(“nCreating round reference:”) node1.reference = node2 node2.reference = node1

print(f“Node 1 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node1) – 1}”) print(f“Node 2 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node2) – 1}”)

# Delete our variables print(“nDeleting our variables:”) del node1 del node2

print(“Objects nonetheless alive! (reference counts aren’t zero)”) print(“They solely reference one another, however counts are nonetheless 1 every”) |

Whenever you attempt to delete these objects, reference counting alone can’t clear them up as a result of they maintain one another alive. Even when no exterior variables reference them, they nonetheless have references from one another. So their reference rely by no means reaches zero.

Output:

|

Creating two nodes:

Creating round reference: Node 1 refcount: 2 Node 2 refcount: 2

Deleting our variables: Objects nonetheless alive! (reference counts aren‘t zero) They solely reference every different, however counts are nonetheless 1 every |

Right here’s an in depth evaluation of why reference counting received’t work right here:

- After we delete

node1andnode2variables, the objects nonetheless exist in reminiscence - Node 1’s object has a reference (from Node 2’s

.referenceattribute) - Node 2’s object has a reference (from Node 1’s

.referenceattribute) - Every object’s reference rely is 1 (not 0), in order that they aren’t freed

- However no code can attain these objects anymore! They’re rubbish, however reference counting can’t detect it.

For this reason Python wants a second rubbish assortment mechanism to search out and clear up these cycles. Right here’s how one can manually set off rubbish assortment to search out the cycle and delete the objects like so:

|

print(“nTriggering rubbish assortment:”) collected = gc.gather() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”) |

This outputs:

|

Triggering rubbish assortment: Deleting Node 1 Deleting Node 2 Collected 2 objects |

Utilizing Python’s gc Module to Examine Assortment

The gc module helps you to management and examine Python’s rubbish collector:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 |

import gc

# Examine if computerized assortment is enabled print(f“GC enabled: {gc.isenabled()}”)

# Get assortment thresholds thresholds = gc.get_threshold() print(f“nCollection thresholds: {thresholds}”) print(f” Era 0 threshold: {thresholds[0]} objects”) print(f” Era 1 threshold: {thresholds[1]} collections”) print(f” Era 2 threshold: {thresholds[2]} collections”)

# Get present assortment counts counts = gc.get_count() print(f“nCurrent counts: {counts}”) print(f” Gen 0: {counts[0]} objects”) print(f” Gen 1: {counts[1]} collections since final Gen 1″) print(f” Gen 2: {counts[2]} collections since final Gen 2″)

# Manually set off assortment and see what was collected print(f“nCollecting rubbish…”) collected = gc.gather() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”)

# Get checklist of all tracked objects all_objects = gc.get_objects() print(f“nTotal tracked objects: {len(all_objects)}”) |

Python makes use of three “generations” for rubbish assortment.

- New objects begin in technology 0.

- Objects that survive a set are promoted to technology 1, and ultimately technology 2.

The concept is that objects which have lived longer are much less more likely to be rubbish.

Whenever you run the above code, you must see one thing like this:

|

GC enabled: True

Assortment thresholds: (700, 10, 10) Era 0 threshold: 700 objects Era 1 threshold: 10 collections Era 2 threshold: 10 collections

Present counts: (423, 3, 1) Gen 0: 423 objects Gen 1: 3 collections since final Gen 1 Gen 2: 1 collections since final Gen 2

Accumulating rubbish... Collected 0 objects

Complete tracked objects: 8542 |

The thresholds decide when every technology is collected. When technology 0 has 700 objects, a set is triggered. After 10 technology 0 collections, technology 1 is collected. After 10 technology 1 collections, technology 2 is collected.

Conclusion

Python’s rubbish assortment combines reference counting for quick cleanup with cyclic rubbish assortment for round references. Listed here are the important thing takeaways:

- Variables are pointers to things, not containers holding values.

- Reference counting tracks what number of pointers level to every object. Objects are freed instantly when reference rely reaches zero.

- Round references occur when objects level to one another in a cycle. Reference counting can’t deal with round references (counts by no means attain zero).

- Generational rubbish assortment finds and cleans up round references. There are three generations: 0 (younger), 1, 2 (previous).

- Use

gc.gather()to manually set off assortment.

Understanding that variables are pointers (not containers) and figuring out what round references are helps you write higher code and debug reminiscence points.

I mentioned “Every little thing you Must Know…” within the title, I do know. However there’s extra (there at all times is) you’ll be able to be taught comparable to how weak references work. A weak reference permits you to consult with or level to an object with out growing its reference rely. Certain, such references add extra complexity to the image however understanding weak references and debugging reminiscence leaks in your Python code are a number of subsequent steps value exploring for curious readers. Completely satisfied exploring!

On this article, you’ll find out how Python allocates, tracks, and reclaims reminiscence utilizing reference counting and generational rubbish assortment, and the right way to examine this habits with the gc module.

Matters we’ll cowl embody:

- The position of references and the way Python’s reference counts change in widespread eventualities.

- Why round references trigger leaks underneath pure reference counting, and the way cycles are collected.

- Sensible use of the

gcmodule to watch thresholds, counts, and assortment.

Let’s get proper to it.

Every little thing You Must Know About How Python Manages Reminiscence

Picture by Editor

Introduction

In languages like C, you manually allocate and free reminiscence. Neglect to free reminiscence and you’ve got a leak. Free it twice and your program crashes. Python handles this complexity for you thru computerized rubbish assortment. You create objects, use them, and once they’re not wanted, Python cleans them up.

However “computerized” doesn’t imply “magic.” Understanding how Python’s rubbish collector works helps you write extra environment friendly code, debug reminiscence leaks, and optimize performance-critical purposes. On this article, we’ll discover reference counting, generational rubbish assortment, and the right way to work with Python’s gc module. Right here’s what you’ll be taught:

- What references are, and the way reference counting works in Python

- What round references are and why they’re problematic

- Python’s generational rubbish assortment

- Utilizing the

gcmodule to examine and management assortment

Let’s get to it.

What Are References in Python?

Earlier than we transfer to rubbish assortment, we have to perceive what “references” really are.

Whenever you write this:

Right here’s what really occurs:

- Python creates an integer object 123 someplace in reminiscence

- The variable

xshops a pointer to that object’s reminiscence location xdoesn’t “comprise” the integer worth — it factors to it

So in Python, variables are labels, not containers. Variables don’t maintain values; they’re names that time to things in reminiscence. Consider objects as balloons floating in reminiscence, and variables as strings tied to these balloons. A number of strings could be tied to the identical balloon.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

# Create an object my_list = [1, 2, 3] # my_list factors to an inventory object in reminiscence

# Create one other reference to the SAME object another_name = my_checklist # another_name factors to the identical checklist

# They each level to the identical object print(my_list is another_name) print(id(my_list) == id(another_name))

# Modifying by way of one impacts the opposite (identical object!) my_list.append(4) print(another_name)

# However reassigning creates a NEW reference my_list = [5, 6, 7] # my_list now factors to a DIFFERENT object print(another_name) |

Whenever you write another_name = my_list, you’re not copying the checklist. You’re creating one other pointer to the identical object. Each variables reference (level to) the identical checklist in reminiscence. That’s why adjustments by way of one variable seem within the different. So the above code offers you the next output:

|

True True [1, 2, 3, 4] [1, 2, 3, 4] |

The id() operate reveals the reminiscence handle of an object. When two variables have the identical id(), they reference the identical object.

Okay, However What Is a “Round” Reference?

A round reference happens when objects reference one another, forming a cycle. Right here’s an excellent easy instance:

|

class Particular person: def __init__(self, title): self.title = title self.buddy = None # Will retailer a reference to a different Particular person

# Create two individuals alice = Particular person(“Alice”) bob = Particular person(“Bob”)

# Make them associates – this creates a round reference alice.buddy = bob # Alice’s object factors to Bob’s object bob.buddy = alice # Bob’s object factors to Alice’s object |

Now now we have a cycle: alice → Particular person(“Alice”) → .buddy → Particular person(“Bob”) → .buddy → Particular person(“Alice”) → …

Right here’s why it’s known as “round” (in case you haven’t guessed but). In the event you observe the references, you go in a circle: Alice’s object references Bob’s object, which references Alice’s object, which references Bob’s object… without end. It’s a loop.

How Python Manages Reminiscence Utilizing Reference Counting & Generational Rubbish Assortment

Python makes use of two most important mechanisms for rubbish assortment:

- Reference counting: That is the first methodology. Objects are deleted when their reference rely reaches zero.

- Generational rubbish assortment: A backup system that finds and cleans up round references that reference counting can’t deal with.

Let’s discover each intimately.

How Reference Counting Works

Each Python object has a reference rely which is the variety of references to it, which means variables (or different objects) pointing to it. When the reference rely reaches zero, the reminiscence is instantly freed.

|

import sys

# Create an object – reference rely is 1 my_list = [1, 2, 3] print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Create one other reference – rely will increase another_ref = my_list print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete one reference – rely decreases del another_ref print(f“Reference rely: {sys.getrefcount(my_list)}”)

# Delete the final reference – object is destroyed del my_list |

Output:

|

Reference rely: 2 Reference rely: 3 Reference rely: 2 |

Right here’s how reference counting works. Python retains a counter on each object monitoring what number of references level to it. Every time you:

- Assign the item to a variable → rely will increase

- Go it to a operate → rely will increase briefly

- Retailer it in a container → rely will increase

- Delete a reference → rely decreases

When the rely hits zero (no references left), Python instantly frees the reminiscence.

📑 About

sys.getrefcount(): The rely proven bysys.getrefcount()is at all times 1 larger than you anticipate as a result of passing the item to the operate creates a brief reference. In the event you see “2”, there’s actually just one exterior reference.

Instance: Reference Counting in Motion

Let’s see reference counting in motion with a customized class that says when it’s deleted.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

class DataObject: “”“Object that says when it is created and destroyed”“”

def __init__(self, title): self.title = title print(f“Created {self.title}”)

def __del__(self): “”“Referred to as when object is about to be destroyed”“” print(f“Deleting {self.title}”)

# Create and instantly lose reference print(“Creating object 1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 1”)

print(“nCreating object 2 and deleting it:”) obj2 = DataObject(“Object 2”) del obj2

print(“nReassigning obj1:”) obj1 = DataObject(“Object 3”)

print(“nFunction scope take a look at:”) def create_temporary(): temp = DataObject(“Momentary”) print(“Inside operate”)

create_temporary() print(“After operate”)

print(“nScript ending…”) |

Right here, the __del__ methodology (destructor) is known as when an object’s reference rely reaches zero. With reference counting, this occurs instantly.

Output:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

Creating object 1: Created Object 1

Creating object 2 and deleting it: Created Object 2 Deleting Object 2

Reassigning obj1: Created Object 3 Deleting Object 1

Perform scope take a look at: Created Momentary Inside operate Deleting Momentary After operate

Script ending... Deleting Object 3 |

Discover that Momentary is deleted as quickly because the operate exits as a result of the native variable temp goes out of scope. When temp disappears, there aren’t any extra references to the item, so it’s instantly freed.

How Python Handles Round References

In the event you’ve adopted alongside fastidiously, you’ll see that reference counting can’t deal with round references. Let’s see why.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

import gc import sys

class Node: def __init__(self, title): self.title = title self.reference = None

def __del__(self): print(f“Deleting {self.title}”)

# Create two separate objects print(“Creating two nodes:”) node1 = Node(“Node 1”) node2 = Node(“Node 2”)

# Now create the round reference print(“nCreating round reference:”) node1.reference = node2 node2.reference = node1

print(f“Node 1 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node1) – 1}”) print(f“Node 2 refcount: {sys.getrefcount(node2) – 1}”)

# Delete our variables print(“nDeleting our variables:”) del node1 del node2

print(“Objects nonetheless alive! (reference counts aren’t zero)”) print(“They solely reference one another, however counts are nonetheless 1 every”) |

Whenever you attempt to delete these objects, reference counting alone can’t clear them up as a result of they maintain one another alive. Even when no exterior variables reference them, they nonetheless have references from one another. So their reference rely by no means reaches zero.

Output:

|

Creating two nodes:

Creating round reference: Node 1 refcount: 2 Node 2 refcount: 2

Deleting our variables: Objects nonetheless alive! (reference counts aren‘t zero) They solely reference every different, however counts are nonetheless 1 every |

Right here’s an in depth evaluation of why reference counting received’t work right here:

- After we delete

node1andnode2variables, the objects nonetheless exist in reminiscence - Node 1’s object has a reference (from Node 2’s

.referenceattribute) - Node 2’s object has a reference (from Node 1’s

.referenceattribute) - Every object’s reference rely is 1 (not 0), in order that they aren’t freed

- However no code can attain these objects anymore! They’re rubbish, however reference counting can’t detect it.

For this reason Python wants a second rubbish assortment mechanism to search out and clear up these cycles. Right here’s how one can manually set off rubbish assortment to search out the cycle and delete the objects like so:

|

print(“nTriggering rubbish assortment:”) collected = gc.gather() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”) |

This outputs:

|

Triggering rubbish assortment: Deleting Node 1 Deleting Node 2 Collected 2 objects |

Utilizing Python’s gc Module to Examine Assortment

The gc module helps you to management and examine Python’s rubbish collector:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 |

import gc

# Examine if computerized assortment is enabled print(f“GC enabled: {gc.isenabled()}”)

# Get assortment thresholds thresholds = gc.get_threshold() print(f“nCollection thresholds: {thresholds}”) print(f” Era 0 threshold: {thresholds[0]} objects”) print(f” Era 1 threshold: {thresholds[1]} collections”) print(f” Era 2 threshold: {thresholds[2]} collections”)

# Get present assortment counts counts = gc.get_count() print(f“nCurrent counts: {counts}”) print(f” Gen 0: {counts[0]} objects”) print(f” Gen 1: {counts[1]} collections since final Gen 1″) print(f” Gen 2: {counts[2]} collections since final Gen 2″)

# Manually set off assortment and see what was collected print(f“nCollecting rubbish…”) collected = gc.gather() print(f“Collected {collected} objects”)

# Get checklist of all tracked objects all_objects = gc.get_objects() print(f“nTotal tracked objects: {len(all_objects)}”) |

Python makes use of three “generations” for rubbish assortment.

- New objects begin in technology 0.

- Objects that survive a set are promoted to technology 1, and ultimately technology 2.

The concept is that objects which have lived longer are much less more likely to be rubbish.

Whenever you run the above code, you must see one thing like this:

|

GC enabled: True

Assortment thresholds: (700, 10, 10) Era 0 threshold: 700 objects Era 1 threshold: 10 collections Era 2 threshold: 10 collections

Present counts: (423, 3, 1) Gen 0: 423 objects Gen 1: 3 collections since final Gen 1 Gen 2: 1 collections since final Gen 2

Accumulating rubbish... Collected 0 objects

Complete tracked objects: 8542 |

The thresholds decide when every technology is collected. When technology 0 has 700 objects, a set is triggered. After 10 technology 0 collections, technology 1 is collected. After 10 technology 1 collections, technology 2 is collected.

Conclusion

Python’s rubbish assortment combines reference counting for quick cleanup with cyclic rubbish assortment for round references. Listed here are the important thing takeaways:

- Variables are pointers to things, not containers holding values.

- Reference counting tracks what number of pointers level to every object. Objects are freed instantly when reference rely reaches zero.

- Round references occur when objects level to one another in a cycle. Reference counting can’t deal with round references (counts by no means attain zero).

- Generational rubbish assortment finds and cleans up round references. There are three generations: 0 (younger), 1, 2 (previous).

- Use

gc.gather()to manually set off assortment.

Understanding that variables are pointers (not containers) and figuring out what round references are helps you write higher code and debug reminiscence points.

I mentioned “Every little thing you Must Know…” within the title, I do know. However there’s extra (there at all times is) you’ll be able to be taught comparable to how weak references work. A weak reference permits you to consult with or level to an object with out growing its reference rely. Certain, such references add extra complexity to the image however understanding weak references and debugging reminiscence leaks in your Python code are a number of subsequent steps value exploring for curious readers. Completely satisfied exploring!