is a part of a collection about distributed AI throughout a number of GPUs:

- Half 1: Understanding the Host and System Paradigm (this text)

- Half 2: Level-to-Level and Collective Operations (coming quickly)

- Half 3: How GPUs Talk (coming quickly)

- Half 4: Gradient Accumulation & Distributed Information Parallelism (DDP) (coming quickly)

- Half 5: ZeRO (coming quickly)

- Half 6: Tensor Parallelism (coming quickly)

Introduction

This information explains the foundational ideas of how a CPU and a discrete graphics card (GPU) work collectively. It’s a high-level introduction designed that can assist you construct a psychological mannequin of the host-device paradigm. We’ll focus particularly on NVIDIA GPUs, that are probably the most generally used for AI workloads.

For built-in GPUs, akin to these present in Apple Silicon chips, the structure is barely completely different, and it gained’t be lined on this put up.

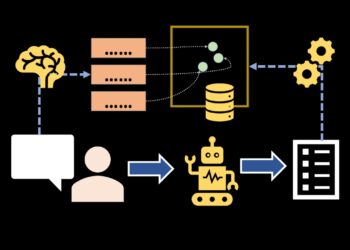

The Large Image: The Host and The System

A very powerful idea to understand is the connection between the Host and the System.

- The Host: That is your CPU. It runs the working system and executes your Python script line by line. The Host is the commander; it’s answerable for the general logic and tells the System what to do.

- The System: That is your GPU. It’s a robust however specialised coprocessor designed for massively parallel computations. The System is the accelerator; it doesn’t do something till the Host offers it a process.

Your program all the time begins on the CPU. Once you need the GPU to carry out a process, like multiplying two giant matrices, the CPU sends the directions and the info over to the GPU.

The CPU-GPU Interplay

The Host talks to the System via a queuing system.

- CPU Initiates Instructions: Your script, operating on the CPU, encounters a line of code meant for the GPU (e.g.,

tensor.to('cuda')). - Instructions are Queued: The CPU doesn’t wait. It merely locations this command onto a particular to-do checklist for the GPU referred to as a CUDA Stream — extra on this within the subsequent part.

- Asynchronous Execution: The CPU doesn’t watch for the precise operation to be accomplished by the GPU, the host strikes on to the subsequent line of your script. That is referred to as asynchronous execution, and it’s a key to reaching excessive efficiency. Whereas the GPU is busy crunching numbers, the CPU can work on different duties, like getting ready the subsequent batch of information.

CUDA Streams

A CUDA Stream is an ordered queue of GPU operations. Operations submitted to a single stream execute so as, one after one other. Nonetheless, operations throughout completely different streams can execute concurrently — the GPU can juggle a number of unbiased workloads on the similar time.

By default, each PyTorch GPU operation is enqueued on the present lively stream (it’s often the default stream which is robotically created). That is easy and predictable: each operation waits for the earlier one to complete earlier than beginning. For many code, you by no means discover this. But it surely leaves efficiency on the desk when you’ve work that might overlap.

A number of Streams: Concurrency

The traditional use case for a number of streams is overlapping computation with knowledge transfers. Whereas the GPU processes batch N, you’ll be able to concurrently copy batch N+1 from CPU RAM to GPU VRAM:

Stream 0 (compute): [process batch 0]────[process batch 1]───

Stream 1 (knowledge): ────[copy batch 1]────[copy batch 2]───This pipeline is feasible as a result of compute and knowledge switch occur on separate {hardware} models contained in the GPU, enabling true parallelism. In PyTorch, you create streams and schedule work onto them with context managers:

compute_stream = torch.cuda.Stream()

transfer_stream = torch.cuda.Stream()

with torch.cuda.stream(transfer_stream):

# Enqueue the switch on transfer_stream

next_batch = next_batch_cpu.to('cuda', non_blocking=True)

with torch.cuda.stream(compute_stream):

# This runs concurrently with the switch above

output = mannequin(current_batch)Observe the non_blocking=True flag on .to(). With out it, the switch would nonetheless block the CPU thread even while you intend it to run asynchronously.

Synchronization Between Streams

Since streams are unbiased, it is advisable to explicitly sign when one depends upon one other. The blunt instrument is:

torch.cuda.synchronize() # waits for ALL streams on the machine to completeA extra surgical strategy makes use of CUDA Occasions. An occasion marks a particular level in a stream, and one other stream can wait on it with out halting the CPU thread:

occasion = torch.cuda.Occasion()

with torch.cuda.stream(transfer_stream):

next_batch = next_batch_cpu.to('cuda', non_blocking=True)

occasion.report() # mark: switch is completed

with torch.cuda.stream(compute_stream):

compute_stream.wait_event(occasion) # do not begin till switch completes

output = mannequin(next_batch)That is extra environment friendly than stream.synchronize() as a result of it solely stalls the dependent stream on the GPU facet — the CPU thread stays free to maintain queuing work.

For day-to-day PyTorch coaching code you gained’t have to handle streams manually. However options like DataLoader(pin_memory=True) and prefetching rely closely on this mechanism underneath the hood. Understanding streams helps you acknowledge why these settings exist and offers you the instruments to diagnose delicate efficiency bottlenecks after they seem.

PyTorch Tensors

PyTorch is a robust framework that abstracts away many particulars, however this abstraction can generally obscure what is occurring underneath the hood.

Once you create a PyTorch tensor, it has two elements: metadata (like its form and knowledge kind) and the precise numerical knowledge. So while you run one thing like this t = torch.randn(100, 100, machine=machine), the tensor’s metadata is saved within the host’s RAM, whereas its knowledge is saved within the GPU’s VRAM.

This distinction is essential. Once you run print(t.form), the CPU can instantly entry this data as a result of the metadata is already in its personal RAM. However what occurs for those who run print(t), which requires the precise knowledge dwelling in VRAM?

Host-System Synchronization

Accessing GPU knowledge from the CPU can set off a Host-System Synchronization, a standard efficiency bottleneck. This happens at any time when the CPU wants a outcome from the GPU that isn’t but accessible within the CPU’s RAM.

For instance, contemplate the road print(gpu_tensor) which prints a tensor that’s nonetheless being computed by the GPU. The CPU can’t print the tensor’s values till the GPU has completed all of the calculations to acquire the ultimate outcome. When the script reaches this line, the CPU is compelled to block, i.e. it stops and waits for the GPU to complete. Solely after the GPU completes its work and copies the info from its VRAM to the CPU’s RAM can the CPU proceed.

As one other instance, what’s the distinction between torch.randn(100, 100).to(machine) and torch.randn(100, 100, machine=machine)? The primary methodology is much less environment friendly as a result of it creates the info on the CPU after which transfers it to the GPU. The second methodology is extra environment friendly as a result of it creates the tensor immediately on the GPU; the CPU solely sends the creation command.

These synchronization factors can severely influence efficiency. Efficient GPU programming entails minimizing them to make sure each the Host and System keep as busy as attainable. In spite of everything, you need your GPUs to go brrrrr.

Scaling Up: Distributed Computing and Ranks

Coaching giant fashions, akin to Giant Language Fashions (LLMs), typically requires extra compute energy than a single GPU can provide. Coordinating work throughout a number of GPUs brings you into the world of distributed computing.

On this context, a brand new and essential idea emerges: the Rank.

- Every rank is a CPU course of which will get assigned a single machine (GPU) and a singular ID. When you launch a coaching script throughout two GPUs, you’ll create two processes: one with

rank=0and one other withrank=1.

This implies you’re launching two separate situations of your Python script. On a single machine with a number of GPUs (a single node), these processes run on the identical CPU however stay unbiased, with out sharing reminiscence or state. Rank 0 instructions its assigned GPU (cuda:0), whereas Rank 1 instructions one other GPU (cuda:1). Though each ranks run the identical code, you’ll be able to leverage a variable that holds the rank ID to assign completely different duties to every GPU, like having each course of a distinct portion of the info (we’ll see examples of this within the subsequent weblog put up of this collection).

Conclusion

Congratulations for studying all the way in which to the tip! On this put up, you realized about:

- The Host/System relationship

- Asynchronous execution

- CUDA Streams and the way they allow concurrent GPU work

- Host-System synchronization

Within the subsequent weblog put up, we are going to dive deeper into Level-to-Level and Collective Operations, which allow a number of GPUs to coordinate complicated workflows akin to distributed neural community coaching.